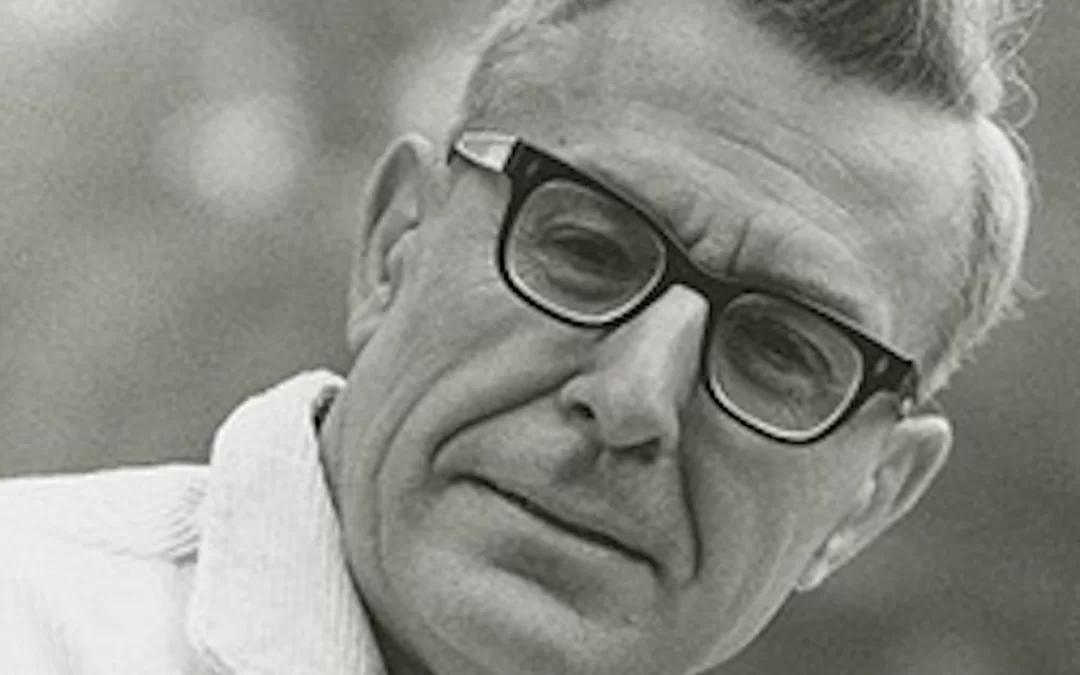

Loren Eiseley (1907-1977) was a Professor of Anthropology at U Penn, in the same department as my brother Ward Goodenough. In a tribute to Eiseley, Ward wrote: “In his writings, Loren Eiseley revealed the feelings and the wonder that inspire many scientists in their work but that most scientists are unable or unwilling to write about. He was at once an anthropologist of science and the scientist’s bard.” This perspective was also voiced in The Bloomsbury Review: “There can be no question that Loren Eiseley maintains a place of eminence among nature writers. His extended explorations of human life and mind, set against the backdrop of our own and other universes, are like those to be found in every book of nature writing currently available… We now routinely expect our nature writers to leap across the chasm between science, natural history, and poetry with grace and ease… His writing delivered science to non-scientists in the lyrical language of earthly metaphor, irony, simile, and narrative, all paced like a good mystery.”

Here’s some vintage Eiseley:

I am treading deeper and deeper into leaves and silence. I see more faces watching, non-human faces. Ironically, I who profess no religion find the whole of my life a religious pilgrimage.

The religious forms of the present leave me unmoved. My eye is round, open, and undomesticated as an owl’s in a primeval forest — a world that for me has never truly departed.

Every time we walk along a beach some ancient urge disturbs us so that we find ourselves shedding shoes and garments or scavenging among seaweed and whitened timbers like the homesick refugees of a long war.

We are rag dolls made out of many ages and skins, changelings who have slept in wood nests or hissed in the uncouth guise of waddling amphibians. We have played such roles for infinitely longer ages than we have been men. Our identity is a dream.

The truth is, however, that there is nothing very “normal” about nature. Once upon a time there were no flowers at all.

We are one of many appearances of the thing called Life; we are not its perfect image, for it has no perfect image except Life, and life is multitudinous and emergent in the stream of time.

We forget that nature itself is one vast miracle transcending the reality of night and nothingness… that each one of us in his personal life repeats that miracle.

Man no longer dreams over a book in which a soft voice, a constant companion, observes, exhorts, or sighs with him through the pangs of youth and age. Today he is more likely to sit before a screen and dream the mass dream which comes from outside.

The need is not really for more brains, the need is now for a gentler, a more tolerant people than those who won for us against the ice, the tiger and the bear. The hand that hefted the ax out of some old blind allegiance to the past fondles the machine gun as lovingly. It is a habit man will have to break to survive, but the roots go very deep.