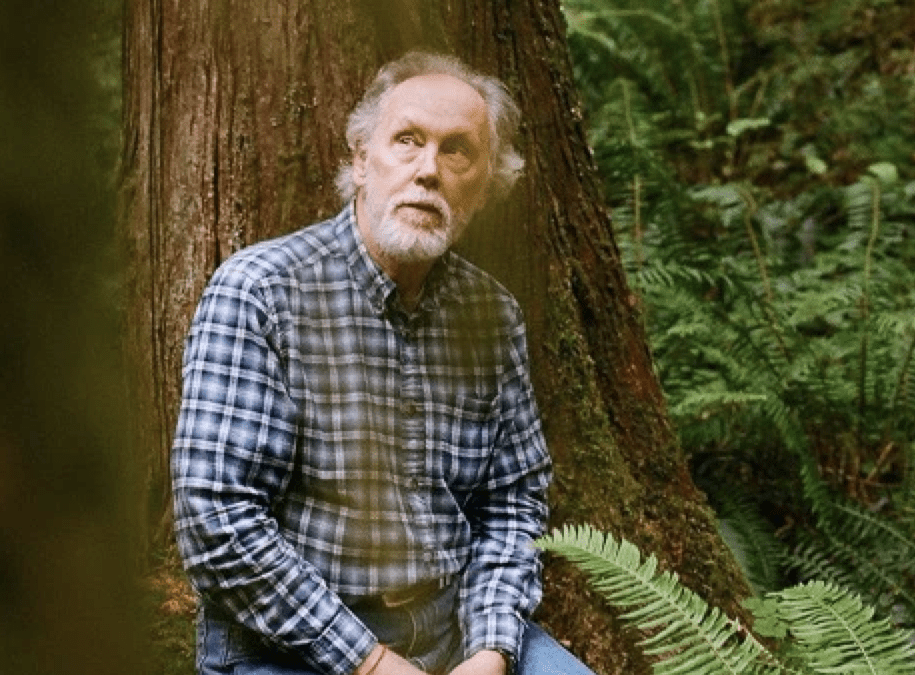

Barry Lopez, educated in the Roman Catholic tradition, spent his life exploring, photographing, and writing lucidly about the wonders of natural world, from the Arctic to the Amazon. A full collection of Lopez wisdom is here; some wonderful examples below.

To put your hands in a river is to feel the chords that bind the earth together.

The land is like poetry: it is inexplicably coherent, it is transcendent in its meaning, and it has the power to elevate a consideration of human life.

One of the great dreams of man must be to find some place between the extremes of nature and civilization where it is possible to live without regret.

We cannot, of course, save the World because we do not have authority over its parts. We can serve the world though. That is everyone’s calling, to lead a life that helps.

I know of no restorative of heart, body, and soul more effective against hopelessness than the restoration of the Earth.

Everything is held together with stories. That is all that is holding us together, stories and compassion.

Remember on this one thing, said Badger. The stories people tell have a way of taking care of them. If stories come to you, care for them. And learn to give them away where they are needed. Sometimes a person needs a story more than food to stay alive. That is why we put these stories in each others’ memories. This is how people care for themselves.

At the heart of this story, I think, is a simple, abiding belief: it is possible to live wisely on the land, and to live well. And in behaving respectfully toward all that the land contains, it is possible to imagine a stifling ignorance falling away from us.

To allow mystery, which is to say to yourself, “There could be more…things we don’t understand,” is not to damn knowledge. … It is to permit yourself an extraordinary freedom: someone else does not have to be wrong in order that you might be right…. This tolerance for mystery invigorates the imagination; and it is the imagination that gives shape to the universe.

I do not know, really, how we will survive without places like the Inner Gorge of the Grand Canyon to visit. Once in a lifetime, even, is enough. To feel the stripping down, an ebb of the press of conventional time, a radical change of proportion, an unspoken respect for others that elicits keen emotional pleasure, a quick intimate pounding of the heart.

Lying there, I thought of my own culture, of the assembly of books in the library at Alexandria; of the deliberations of Darwin and Mendel in their respective gardens; of the architectural conception of the cathedral at Chartres; of Bach’s cello suites, the philosophy of Schweitzer, the insights of Planck and Dirac. Have we come all this way, I wondered, only to be dismantled by our own technologies, to be betrayed by political connivance or the impersonal avarice of a corporation?

If the real human environment in developed countries today is third-growth monocultured “forests,” tar-sand petroleum, cow-burnt grasslands, and smog-like clouds of microplastics floating in oceans where fish once thrived, then human cultures need to distinguish between sentimentality about loss and the imperative to survive. They need to establish a more relevant politics than the competitive politics of nation-states. And to found economies built not on profit but on conservation.

I arrived always at the same, disquieting place: the history of Western exploration in the New World in every quarter is a confrontation with an image of distant wealth. Gold, furs, timber, whales, the Elysian Fields, the control of trade routes to the Orient—it all had to be verified, acquired, processed, allocated, and defended. And these far-flung enterprises had to be profitable, or be made to seem profitable, or be financed until they were. The task was wild, extraordinary. And it was complicated by the fact that people were living in North America when we arrived. Their title to the wealth had to be extinguished.

Imagine a forty-five-year-old male fifty feet long, a slim, shiny black animal cutting the surface of green ocean water at twenty knots. At fifty tons it is the largest carnivore on earth. Imagine a four-hundred-pound heart the size of a chest of drawers driving five gallons of blood at a stroke through its aorta; a meal of forty salmon moving slowly down twelve-hundred feet of intestine…the sperm whale’s brain is larger than the brain of any other creature that ever lived…With skin as sensitive as the inside of your wrist.

Only the misled can insist that heaven awaits the righteous while they watch the fires on Earth consume the only heaven we have ever known.

Because mankind can circumvent evolutionary law, it is incumbent upon him, say evolutionary biologists, to develop another law to abide by if he wishes to survive, to not outstrip his food base. He must learn restraint.