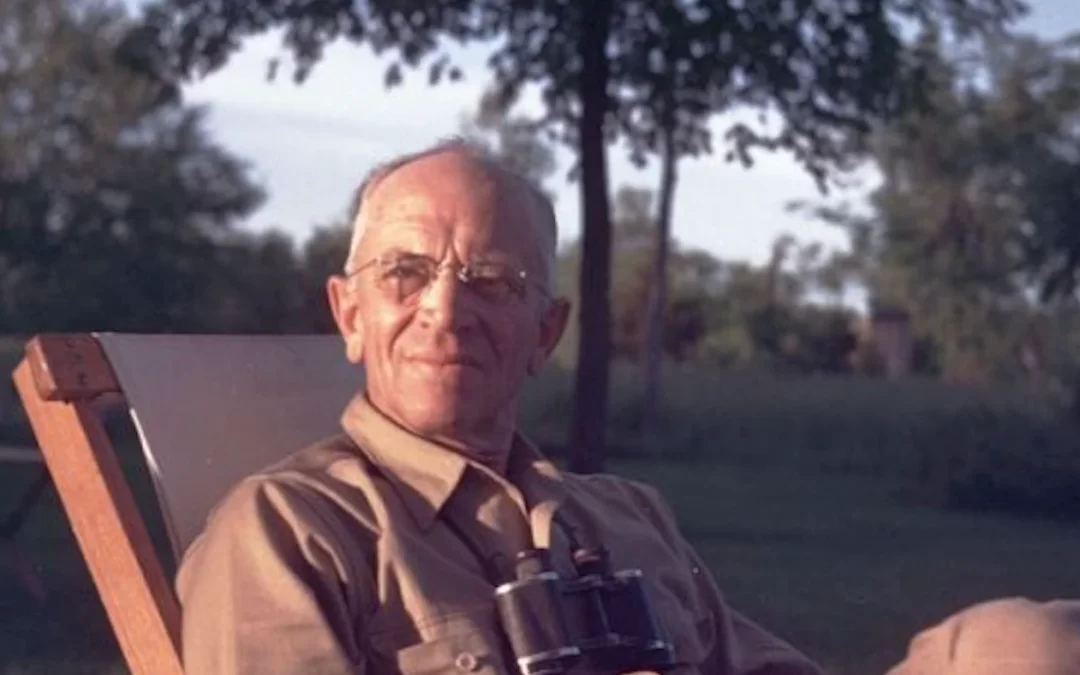

We began this series of Religious Naturalist Voices with Rachel Carson (1907-1964), the inspiration and embodiment of environmental activism. Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) whose 1949 collection of essays, A Sand County Almanac, has sold millions of copies, is considered by many to have fathered the conservation movement. Nature poet Wendell Berry writes: “Of all the conservationists who have preceded us, Leopold was the most radical, the most complete, and therefore the most needed.”

Leopold articulated the concept of a Land Ethic, which he describes thusly:

All ethics so far evolved rest upon a single premise; that the individual is a member of a community of interdependent parts. The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soil, water, plants and animals, or collectively: the land. This sounds simple: do we not already sing our love for and obligation to the land of the free and the home of the brave? Yes, but just what and whom do we love? Certainly not the soil, which we are sending helter-skelter down river. Certainly not the waters, which we assume have no function except to turn turbines, float barges, and carry off sewage. Certainly not the plants, of which we exterminate whole communities without batting an eye. Certainly not the animals, of which we have already extirpated many of the largest and most beautiful species. A land ethic of course cannot prevent the alteration, management, and use of these ‘resources,’ but it does affirm their right to continued existence, and, at least in spots, their continued existence in a natural state. In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such.

A land ethic, then, reflects the existence of an ecological conscience – and this in turn reflects a conviction of individual responsibility for the health of the land. Health is the capacity of the land for self-renewal. Conservation is our effort to understand and preserve this capacity.

That land is a community is the basic concept of ecology, but that land is to be loved and respected is an extension of ethics.

Here are some more wonderful Aldo Leopold quotes — and keep in mind that he was writing some 80 years ago.

It is inconceivable to me that an ethical relation to land can exist without love, respect, and admiration for land, and a high regard for its value. By value, I of course mean something far broader than mere economic value; I mean value in the philosophical sense.

No important change in ethics was ever accomplished without an internal change in our intellectual emphasis, loyalties, affections, and convictions. The proof that conservation has not yet touched these foundations of conduct lies in the fact that philosophy and religion have not yet heard of it. …We can be ethical only in relation to something we can see, feel, understand, love, or otherwise have faith in.

A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.

Conservation is getting nowhere because it is incompatible with our Abrahamic concept of land. We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.

Our ability to perceive quality in nature begins, as in art, with the pretty. It expands through successive stages of the beautiful to values as yet uncaptured by language.

For one species to mourn the death of another is a new thing under the sun.

One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.

We shall never achieve harmony with the land, any more than we shall achieve absolute justice or liberty for people. In these higher aspirations, the important thing is not to achieve but to strive. … That the situation appears hopeless should not prevent us from doing our best.

The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant, “What good is it?” If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. If the biota, in the course of eons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.

We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes – something known only to her and to the mountain. I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters’ paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.

Wilderness is the raw material out of which man has hammered the artifact called civilization.… Civilization has so cluttered this elemental man-earth relationship with gadgets and middlemen, that awareness of it is growing dim. We fancy that industry supports us, forgetting what supports industry…. Wilderness is a resource which can shrink but not grow… Creation of new wilderness in the full sense of the word is impossible. All conservation of wildness is self-defeating; for to cherish we must see and fondle, and when enough have seen and fondled, there is no wilderness left to cherish.

This leads me to close with Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862): “In wilderness is the preservation of the world.” An interesting and accessible essay considers Thoreau, Leopold and Carson as spokespersons for environmental virtue ethics.